Special Mentions

Kaira Looro 2024

1st Prize -

2nd Prize -

3rd Prize -

Honourable Mentions -

Special Mentions -

Finalists -

Top 50 PAUPOLCZA9195

from Polandproject by Paulina Czaja, Amelia Domisch, Maja Cierpialowska, Nina Borkowska

The proposed maternity centre in Senegal aims to create a sanctuary for pregnant women, combining functionality with a nurturing environment. The entrance serves as a transitional space between the exterior and interior of the facility. Here, the reception area is strategically located, accompanied by a planter equipped with a bench, providing a welcoming atmosphere. This section of the project is sheltered, functioning as a waiting area where visitors can comfortably sit and wait for their appointments, mothers can meet their families, and acquaintances can expect the children together. The indoor part of the project occupies the northern portion of the plot. The design prioritizes straightforward and functional communication, arranged along a single corridor. This layout ensures ease of navigation and efficient movement within the facility. The first part of the interior features the maternal ward and consultation rooms. These spaces are designed to provide a serene and private environment for expecting mothers and to facilitate regular medical check-ups and consultations. Beyond the doors located midway down the corridor lies the sterile section. This area is critical for maintaining high standards of cleanliness and hygiene, which are paramount in a healthcare setting. It features neonatal rooms, operating theaters and a staff room connected with operation room by a transition zone for sanitation. This setup ensures that all medical procedures are conducted in a safe and controlled environment. Recognizing the importance of community and social interaction, the project includes a communal area for mothers. An outdoor kitchen and dining area are provided, where women can prepare meals, dine together, and engage in conversations, fostering a sense of community and support. Additionally, the project envisions an enclosed garden featuring a well. This garden serves multiple purposes: it is a tranquil space for relaxation and reflection and a source of water, reinforcing the centre's self-sustainability. Overall, this maternity centre is designed to be a space for African pregnant women combining practicality with a warm, communal atmosphere. The layout and the inclusion of both functional and social spaces aim to enhance the well-being and comfort of all users. The construction materials for the project are chosen to combine sustainability with high accessibility, enhancing both the functionality and aesthetic appeal of the maternity centre. The walls, with reinforced concrete foundations, are crafted from rammed earth, composed of a mixture of red clay and river sand. In the mothers’ room and staff’s office square holes are to be cut, to provide natural light and ventilation. The roof is an independent structure, supported by wooden beams. It features two asymmetric slopes of sheet metal directing water inward, towards a central gutter. To mitigate the heat absorption of the metal, a layer of reed matting is placed underneath, serving as an effective insulator. Connecting the roof and the walls are see-through panels made from a combination of wood and rattan matting. These panels are adjustable, allowing for flexibility in ventilation and light control, enhancing the comfort within the building. To ensure a comfortable atmosphere, fabric curtains were designed, in the form of long textiles hanging from the wood structure beams. Other than decoration, they provide cooling and scatter the light. The flooring throughout the facility is primarily made of screed, providing a durable and natural surface. The flooring in the kitchen is paved with red brick, offering a rustic yet practical solution. In the operational areas, tiles are used to meet the hygiene and cleanliness standards required for medical procedures. The construction process for the maternity centre involves several key steps to ensure the project is completed efficiently and to a high standard. Initially, trenches need to be dug for the foundations. Once the trenches are ready, wooden formwork is erected. This formwork will be gradually filled with the rammed earth mixture, layer by layer, to create the robust walls of the structure. Following the completion of the walls and the removal of the formwork, the roof construction begins. The roof structure is simple. Wooden beams are assembled to form the roof's frame. Once the beams are in place, a layer of reed matting is attached to provide insulation. Finally, metal sheets are secured over the reed mats to complete the roof assembly. In the entrance, the roof has a hole over the planter - to let the trees go past the height of the rooftop and for the plants to be watered by rain. When the basic structure is finished, the next stage involves interior and exterior finishes. Wooden doors and rattan panels are installed, screed flooring is laid down, and red brick flooring is placed in the kitchen area. Additionally, in the operational areas, interior walls are covered in lime and tile flooring is installed to meet hygiene standards. During this phase, greenery is to be planted in the garden, to create a welcoming and serene environment.

Interview

Can you tell us more about your team?

Can you tell us more about your team?

We are a team of five architecture students studying at the Technical University in Gdańsk. We met on the first day of architecture course and bonded immediately. Since then, we have worked on several projects together. Our cooperation has not only refined our skills but also solidified our bond as a team. Each of us brings a unique set of skills to the table, and in combination with our ability to communicate effectively, we work like a well-oiled machine.

What was your feeling when you knew you were among the top projects of the competition?

The moment we saw our work among the special mentions on the website was unbelievable for us. It truly felt surreal as it was our first big accomplishment. The news filled us with an overwhelming sense of pride and joy, validating every late night and every long-lasting discussion we had during the project. As we celebrate our success, we are already looking ahead to new challenges and opportunities.

Can you briefly explain the concept of your project and which is the relationship between it and the women’s health?

We started by defining the zones and setting priorities, in order to keep the project fully functional and operational rooms sterile. Afterwards, we focused on developing the ideas and searching for the concepts. We wanted our project to be centered around women’s recovery and recognizing the importance of the community and social interactions. Not wanting it to be only about basic needs, we also aimed to create a friendly space which can allow future and freshly-baked mothers to focus on themselves and feel taken care of. To achieve this, we localized some common areas in the project, them being a garden and a kitchen with a dining area. Contrary to this open space, the part with hospital functions is fully closed. It is divided into the clinic zone and the sterile hospital sector. Having this defined, we moved into designing the shape and selecting materials. Our idea was to separate the construction of walls and an elevated rooftop, so they mostly are independent of each other.

Which aspects of a design do you focus more during designing?

For us, the most important aspects in design are: the relationship of the building with the environment and how it can blend in with the landscape or relate to the culture of the users, and a simple functional layout, which we always try to create so that the use is intuitive and logical. Moreover, we try to achieve a sustainable project by buildings that have a low carbon footprint, with environmentally friendly, local materials.

Has your design been inspired by other projects in developing countries or past projects of Kaira Looro?

Yes, we carried out an in-depth analysis of buildings in Senegal, focusing on buildings in a similar theme to the competition. Thanks to this, we were able to choose the right construction and layout of the building, suitable for the climate of Casamance region. We were reviewing the competition works from previous years, but we wanted to do something our way.

How your idea of architecture can improve health in developing countries, and how the local community concerned could perceive this architecture?

Our idea of a maternity hospital can be exemplified in the way of designing the functional layout, where, despite modest conditions, we managed to maintain the highest sterility and separation of “dirty” and “clean” zones. Thanks to this future mothers can see their children in a dignified and secure environment. We would be very pleased if the local community perceived our project as a place where mothers can feel safe and sound, interact with each other and truly feel like their child is being born in the right place.

From your point of view, what are the responsibilities of architects in dealing with complex issues such as health’s rights in developing countries?

A proper design can lead to reducing inequalities in quality healthcare accessibility. Well-designed spaces of public facilities can benefit also the impoverished, while high-standard places can often be attended only by wealthier ones. Architects have the power to significantly improve public health through thoughtful and innovative design of health facilities. This involves creating naturally-lit and well-ventilated spaces, which are essential in reducing the spread of airborne diseases and enhancing the overall well-being of patients and healthcare workers. Designing efficient sanitation facilities within these centres plays a crucial role in promoting hygiene and preventing the spread of infections. Thoughtfully designed zoning can greatly impact public health by encouraging better hygiene practices.

The competition registration fee was devolved to the non-profit organization Balouo Salo that helps people in disadvantage area of Senegal. How has it affected you approach to the competition?

Knowing it goes to a Balouo Salo organization and not for commercial use, we did not hesitate at all. It encouraged us even more to take part and ensured us that this competition aims to make a real change for disadvantaged areas which lack certain facilities.

The aim of the competition is also to give professional opportunities to young architects with internship prize and visibility at international level, and we wish your team the best achievements for your career. How do you think you will be in next 10 years? According to you, can this award affect your future?

In the next 10 years we imagine ourselves to be actively working in the field of architecture. We dream to create our own studio since we share similar views and we work really well together. We hope that, wherever we will be, we will stick together either working or as a group of friends. This early career success can help us build a reputation as talented and innovative architects. Moreover, we believe that it will also enrich our portfolio, which is crucial for future career advancement.

TERLEBHAD1327

from Franceproject by Teresa Haddad, Mazen Sfeir

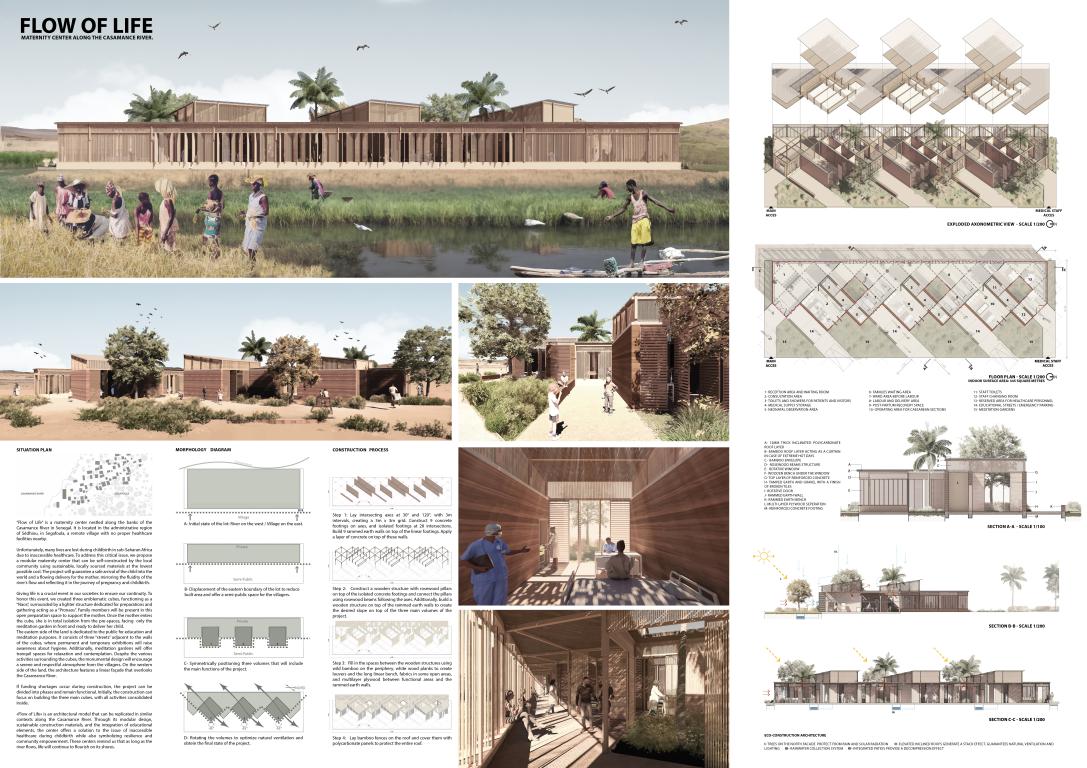

“Flow of Life” is a maternity center nestled along the banks of the Casamance River in Senegal. It is located in the administrative region of Sédhiou, in Segafoula, a remote village with no proper healthcare facilities nearby. Unfortunately, many lives are lost during childbirth in sub-Saharan Africa due to inaccessible healthcare. To address this critical issue, we propose a modular maternity center that can be self-constructed by the local community using sustainable, locally sourced materials at the lowest possible cost. The project will guarantee a safe arrival of the child into the world and a flowing delivery for the mother, mirroring the fluidity of the river's flow and reflecting it in the journey of pregnancy and childbirth. Giving life is a crucial event in our societies to ensure our continuity. To honor this event, we created three emblematic cubes, functioning as a “Naos”, surrounded by a lighter structure dedicated for preparations and gathering acting as a “Pronaos”. Family members will be present in this open preparation space to support the mother. Once the mother enters the cube, she is in total isolation from the pre-spaces, facing only the meditation garden in front and ready to deliver her child. During consultation phases, the mother will visualize and sense the place where she will give birth due to the open space architecture. To facilitate the center’s operation, there are two main entrances to the center: one for the public on the south and another for the medical staff on the north. The eastern side of the land is dedicated to the public for education and meditation purposes. It consists of three “streets” adjacent to the walls of the cubes, where permanent and temporary exhibitions will raise awareness about hygiene. Additionally, meditation gardens will offer tranquil spaces for relaxation and contemplation. Despite the various activities surrounding the cubes, the monumental design will encourage a serene and respectful atmosphere from the villagers. On the western side of the land, the architecture features a linear façade that overlooks the Casamance River. To optimize natural ventilation, the project’s nine main walls are oriented northeast to profit from the dominant winds. This alignment also coincides with the orientation towards Mecca, facilitating prayers for the many inhabitants who practice Islam. The outdoor green spaces merge with the built area, forming a harmonious balance similar to the concept of yin and yang. They also extend and penetrate the structure in patios, providing greenery and natural light in the “Pronaos”. The unobstructed design allows the spaces surrounding the three cubes to be used for communal purposes, such as educational events on annual occasions. If funding shortages occur during construction, the project can be divided into phases and remain functional. Initially, the construction can focus on building the three main cubes, with all activities consolidated inside. "Flow of Life" is an architectural model that can be replicated in similar contexts along the Casamance River. Through its modular design, sustainable construction materials, and the integration of educational elements, the center offers a solution to the issue of inaccessible healthcare during childbirth while also symbolizing resilience and community empowerment. These centers remind us that as long as the river flows, life will continue to flourish on its shores.

Interview with the team

Can you tell us more about your team?

Can you tell us more about your team? We are a team of two architects, Térésa Haddad and Mazen Sfeir, who met 10 years ago during our studies at the Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts. We have always admired each other’s work and shared common beliefs about what architecture should be, which recently led us to combine our forces to create “Unblind Architecture” a project where we turn blind ideas into reality. Currently based between Beirut, Paris, and Montreal, we design and collaborate remotely thanks to the strong chemistry and complementary ways of thinking we share.

Our approach focuses on highlighting concepts and revealing emotions through simple lines. When designing, we aim to be in harmony with nature and imagine ourselves experiencing the journey to adequately address the needs of the users.

What was your feeling when you knew you were among the top projects of the competition?

We were incredibly excited when we received the news, especially because we hold great respect for the jury members and their decisions. "Flow of Life" is a heartfelt solution we developed to address the issue of inaccessible healthcare. Being recognized is incredibly gratifying and reinforces our passion for making a positive impact through architecture.

Can you briefly explain the concept of your project and which is the relationship between it and the women’s health?

Our concept revolves around giving life which is a crucial event in our societies to ensure our continuity. To honour this event, we created three emblematic cubes, functioning as a “Naos”, surrounded by a lighter structure dedicated for preparations and gathering acting as a “Pronaos”. Family members will be present in this open preparation space to support the mother. Once the mother enters the cube, she is in total isolation from the pre-spaces, facing only the meditation garden in front and ready to deliver her child. Flow of Life not only guarantees a safe arrival of the child into the world but also take into consideration women s health, it ensures a flowing delivery for the mother, mirroring the fluidity of the Casamance river's flow and reflecting it in the journey of pregnancy and childbirth.

Which aspects of a design do you focus more during designing? During the design process, we focus on keeping our ideas bold and our lines clear. To achieve this, we continually reassess our concepts as we integrate key parameters: context, functionality, sustainability, user experience, aesthetics, flexibility, and cost. Effective team communication and constructive criticism among members are also essential for achieving the best possible results.

Has your design been inspired by other projects in developing countries or past projects of Kaira Looro?

We drew inspiration from previous Kaira Looro projects to align with the competition's principles. The projects serve as a valuable resource emphasizing the use of sustainable, locally sourced materials that can be self-constructed by local communities at an affordable cost.

How your idea of architecture can improve health in developing countries, and how the local community concerned could perceive this architecture?

"Flow of Life" is an architectural model that can be scaled and replicated in similar contexts along the Casamance River. Through its modular design, sustainable construction materials, and integrated educational elements, the centre provides a solution to healthcare inaccessibility during childbirth while also symbolizing resilience and community empowerment. In cases of funding shortages during construction, the project can be phased. Initially, construction can prioritize building the three main cubes, consolidating all activities inside. The local community will perceive "Flow of Life" centres as a symbol that life will continue to flourish safely on the shores of the Casamance River as long as it flows.

From your point of view, what are the responsibilities of architects in dealing with complex issues such as health’s rights in developing countries?

Architects have a crucial role in addressing the complex issue of healthcare rights in developing countries. This involves ensuring universal access to healthcare, designing flexible spaces that can adapt to evolving needs, and collaborating with health professionals, organizations, and municipalities. Architects should also engage with local communities to understand their health challenges and cultural contexts. By involving community members in the planning process, architects can ensure that designs are inclusive, responsive, and respectful of local customs.

The competition registration fee was devolved to the non-profit organization Balouo Salo that helps people in disadvantage area of Senegal. How has it affected you approach to the competition?

Knowing that our competition registration fee supports the non-profit organization Balouo Salo, which aids disadvantaged communities in Senegal, has deeply influenced our approach to the competition. It brings us immense joy and pride to know that while showcasing our work and competing, we are also making a meaningful contribution to improving lives through architecture.

The aim of the competition is also to give professional opportunities to young architects with internship prize and visibility at international level, and we wish your team the best achievements for your career. How do you think you will be in next 10 years? According to you, can this award affect your future?

In 10 years, we envision “Unblind Architecture”, based between Beirut, Paris and Montreal, helping individuals and communities worldwide unblind their ideas. We aim to listen and collaborate both remotely and on-site to create innovative designs. This award represents significant milestone in our career, validating our capabilities and providing international visibility that enhances our credibility as emerging architects. Ultimately, it inspires us to persist in achieving excellence and making impactful contributions to the field of architecture.

TOMITABAL1998

from Italyproject by Tommaso Balsimelli, Eitaro Francesco Putorti, Paul Lardy, Javier Roig Iglesias

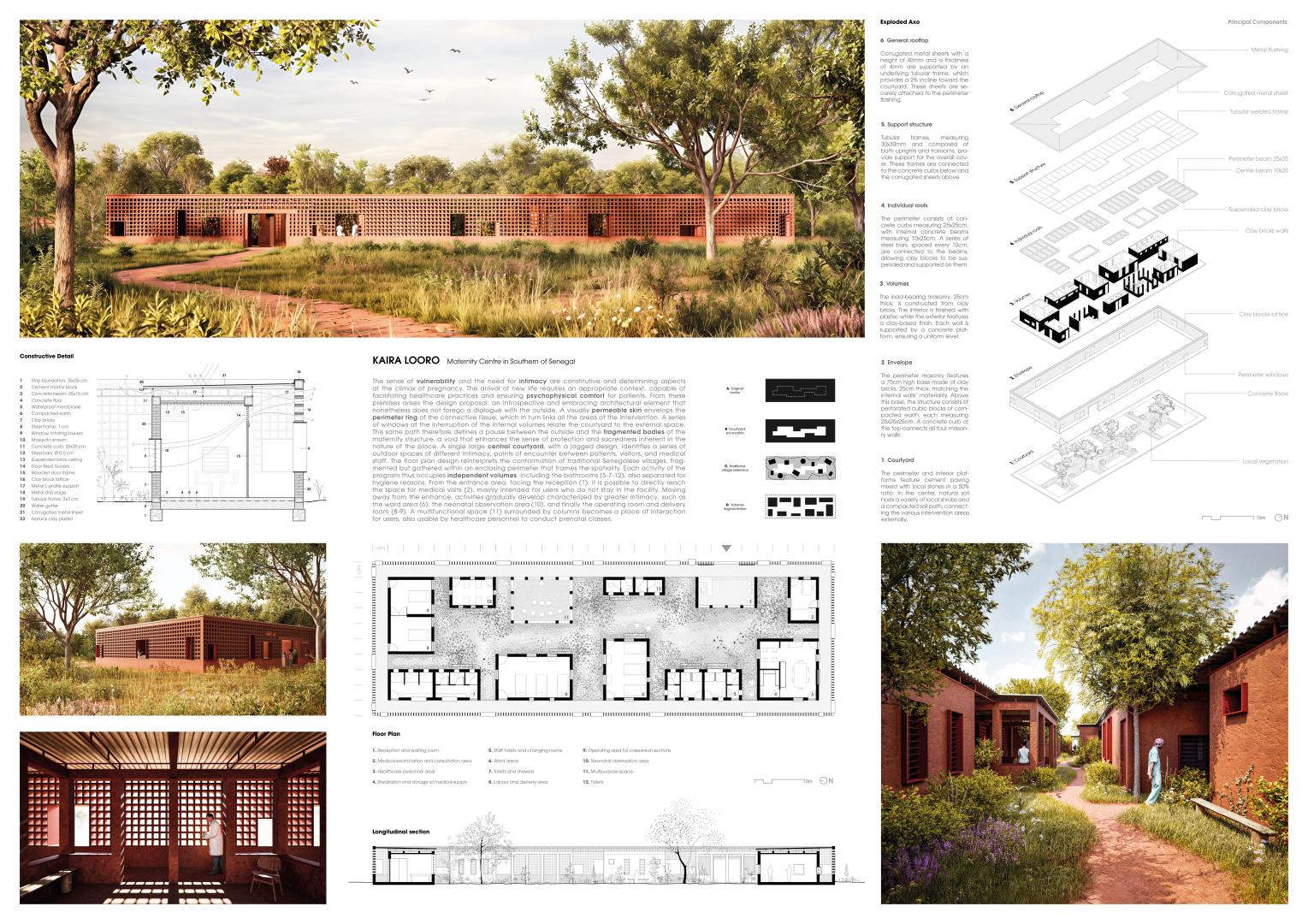

The act of giving birth, a profound and transformative experience, lies at the heart of the proposal for the Maternity Center. This building aims to honor this pivotal moment in a woman’s life by thoughtfully incorporating varying degrees of privacy to serve the functional needs of the center while embracing a spirit of openness and community. At its core, the building features a central courtyard, a serene and intimate space reminiscent of a village square. Here, the informal distribution of vegetation and the use of movable furniture offer opportunities for natural encounters among the people who use the building, fostering a sense of connection. Encircling this central area is a ring of smaller volumes, each containing a distinct part of the program, that provide the first layer of filtering between interior and exterior. A sequence of spaces, nestled between the blocks, serve as semi-private alcoves where one can retreat from the more open, public central space. The rhythm of internal facades does not create a continuous plane around the court but, with varying shifts in the alignment of the blocks, arranges the central space, subtly hinting at a differentiation of its parts without disrupting the unity of the space. The building’s shape and the final layer of filtering are defined by a delicate lattice of clay elements that envelop the volumes, following the contours of the plot. This lattice softly filters the interchange between the interior and exterior. Acting almost as a diaphanous membrane, the clay frames stacked one atop the other embrace the complex, offering privacy and protection when observed from the side, while allowing for unobstructed perpendicular views. Between the lattice and the ring of volumes, a passage connects all the spaces, offering protected paths of circulation at all times. This exterior path follows the lattice, linking the entrances to all the volumes that compose the building. This space can be accessed from the entrance lobby, which opens up to the public part of the central court. From this point, the subpartition of the program is designed to avoid accidental encounters between the public and the more private and intimate uses of the building: on one side, the circulation is dedicated to the medical staff and the medical visit area; on the other, the volumes that are connected are dedicated to more private and intimate uses, such as the labor and delivery area. Following the grid used for the plan layout, a space is left between each pair of volumes to allow for the central spaces and circulation to connect with the peripheral one. This relationship is enhanced in the pavilion area that opens to the exterior, defined only by columns, and becomes part of the more private section of the garden used by the women under care. Here, in the symbolic point of encounter between the public and the intimate, guests can receive visitors during their stay, and the medical staff can give lectures or conduct other didactic activities. In conclusion, the proposal for the Maternity Center seeks to embody a delicate balance between the intimacy of the birthing experience and the aim of maintaining a connection with the exterior space. It aspires to create a thoughtful and inviting environment that fosters community, knowledge exchange, and peaceful contemplation. This holistic approach not only supports the functional needs of the center but also honors the emotional and spiritual aspects of the birthing experience, ensuring that it is respected and celebrated within the fabric of the design.

The building’s materiality is deeply connected to the concept of protecting its interior, which inspired the design proposal. Utilizing earth in various aspects, from finishes to structural components, aims to create a cohesive environment and a distinct indoor experience. This relationship between the container and its contents is established through a tangible recognition of materials. The central courtyard unites all greenery, reaching up to the sky, forming an organic entity. The vertical surfaces, that shape the space following the compositional grid, are marked by the palpable materiality of the earth finishes. The walls then transition from solid to the airy transparency of the brise-soleil along the perimeter made of small square frames of local clay, set upon a solid base. The use of earth as main materiality, with its reddish hue and natural texture, adds life to the spaces without overwhelming them. Moreover, the external space gains complexity through the contrast between the building’s color and the surrounding greenery. The openings, found in both the volumes and the perimeter lattice, are accentuated with steel frames painted to complement the earthy tones of the complex. These frames not only protect the windows but also cast shadows that create patterns on the facades, framing the various views. The interplay of light and shadow adds a dynamic quality to the building’s exterior, and creates a sense of depth. For the roofing, we opted for corrugated steel sheets to facilitate water collection and natural ventilation. The roof, designed as a unitary element, adapts to the volumes that make up the building, joining them and reinforcing the image of the court as a cohesive element. The choice of corrugated steel not only serves functional purposes but also adds a visual contrast with the earthy tones of the walls.

The assembly process of the building begins with the construction of the strip concrete foundations. In order to lower the price, concrete is poured into the trenches along with small rocks that reduce the volume needed to form the foundation. The strips ensure then an omogeneus level and stable base for the upper structure, thanks to two other layers of cement mortar blocks and a reinforced concrete curb. Following the completion of the foundation, clay brick and lattice blocks walls are erected on top, while windows and door openings are framed within the brickwork. Next, reinforced concrete curbs are poured over the top of the brick walls. These curbs provide additional structural support and serve as a transition between the walls and the tubular frame that will support the roof. The ceiling of the various sections is constructed with a series of parallel steel bars connected to the beams to form a unidirectional mesh, on which clay bricks will then be laid. With the curbs in place, a tubular frame is erected over the top to support the corrugated metal roof. The frame is constructed from steel tubes that are welded together. Finally, the corrugated metal roof panels are installed over the tubular frame, providing protection from the elements while allowing for efficient drainage of rainwater. The roof is securely fastened to the frame to ensure a watertight seal and long-lasting performance.

Interview with the team

Can you tell us more about your team?

We are four young architects, between 24 and 26 years old, living and working in Barcelona. Although we come from different countries (Spain, France, and Italy) and universities (Politecnico di Milano and the Technical University of Architecture of Barcelona), our passion for architecture and our shared design philosophy quickly brought us together into this team.

What was your feeling when you knew you were among the top projects of the competition?

It was undoubtedly enjoyable, especially due to the large number of partecipating projects from all over the world.

Can you briefly explain the concept of your project and which is the relationship between it and the women’s health?

The project stems from the desire to empathize psychologically with a woman in the period leading up to childbirth. From this consideration, an architectural proposal takes shape that aims to offer a very perceptible sense of protection, while also striving to define an efficient and logical functional organization to facilitate medical practices.

Which aspects of a design do you focus more during designing?

Obviously, the design aspects to emphasize change from project to project. In our opinion, the true skill of an architect lies in understanding which of these aspects is truly important in the specific context of the intervention. In this case, it was the desire to create a safe, calm, and enveloping space, so the main design aspect was related to spatial perception.

Has your design been inspired by other projects in developing countries or past projects of Kaira Looro?

Since the project theme was new to us, we immediately turned to references in similar contexts, such as Albert Faus and Kéré, especially for construction details and materiality. Developing a proposal in this specific context was very educational and allowed us to learn about numerous new designers and construction techniques.

How your idea of architecture can improve health in developing countries, and how the local community concerned could perceive this architecture?

We strongly believe in the concept of responsible architecture, where the design has positive social, health, technical, and economic impacts on the context in which it is implemented. In the specific scope of this intervention, design strategies such as bioclimatic principles, use of local materials, and community participation are certainly among the key tools that an architect can employ to create a space that is accessible, functional, and integrated within its context.

From your point of view, what are the responsibilities of architects in dealing with complex issues such as health’s rights in developing countries?

If it is true that architecture has the power to improve life for both the individual and the entire community, it is also true the opposite. Many developing countries are filled with poorly designed new buildings that try to emulate the "Western way," disregarding local traditions and identity. Therefore, a good architect has a tremendous responsibility: to deeply understand the context in which they are called to intervene, respecting local traditions and avoiding any semblance of cultural superiority.

The competition registration fee was devolved to the non-profit organization Balouo Salo that helps people in disadvantage area of Senegal. How has it affected you approach to the competition?

Aware of the donation to Balouo Salo, we had no issues with paying the registration fee.

The aim of the competition is also to give professional opportunities to young architects with internship prize and visibility at international level, and we wish your team the best achievements for your career. How do you think you will be in next 10 years? According to you, can this award affect your future?

It's difficult to imagine where we'll be in 10 years in a world changing at an exponential rate. What we do know for certain, however, is that we will be doing our best as architects, perhaps in our own studio. The outcome of this competition will certainly be a significant cultural asset for us, regardless of its actual impact on our careers.

YONMALOOI2436

from Malaysiaproject by Yong Rong Ooi

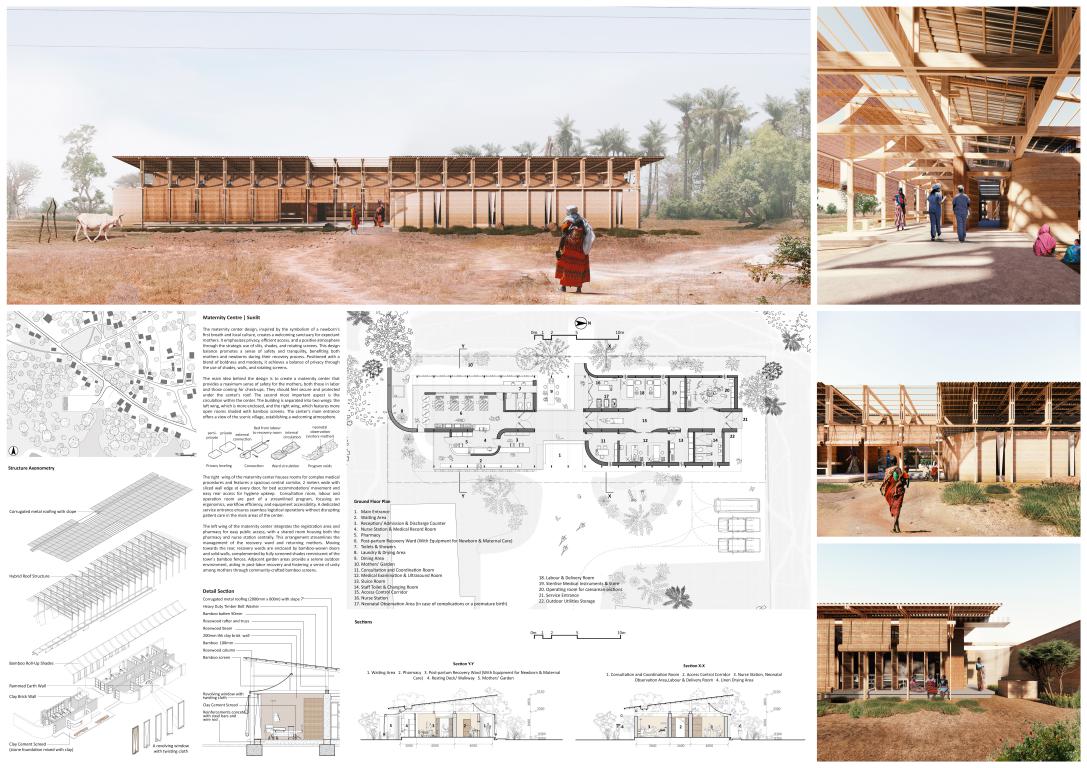

The sun emerges like the first breath of a newborn, casting a soft, golden light like a tender glow that envelops the world in warmth and love. The design of the maternity center beautifully honors the vibrant symbol of local culture and community. It embraces the essence of motherhood and warmly welcomes expectant mothers, offering them a sanctuary of safety and tranquility. The slits and shades allow natural sunlight to enter the recovery wards and garden area. This natural light not only brightens the space but also contributes to a positive and uplifting atmosphere, aiding in the recovery process for mothers and newborns. This reinterpretation prioritizes mothers' privacy and streamlines access and processes to aid the medical care provided to patients. Positioned with a blend of boldness and modesty, it achieves a balance of privacy using shades, walls, and rotating screens. The main idea behind the design is to create a maternity center that provides a maximum sense of safety for the mothers, both those in labor and those coming for check-ups. They should feel secure and protected under the center's roof. The second most important aspect is the circulation within the center. Spaces are carefully planned to ensure efficient circulation and access for patients and medical staff. For example, the separation of the building into two wings—right wing: one more enclosed for medical procedures and another, left wing: with rooms shaded by bamboo screens—optimizes privacy, comfort, and functionality. The center's main entrance offers a view of the scenic village, establishing a welcoming atmosphere. The right wing contains rooms for complex medical procedures. It includes a spacious central corridor measuring 2 meters wide, designed to accommodate beds and allow easy access to the rear of the facility for hygiene maintenance purposes. The doors of the operation room and delivery room are specifically designed to facilitate the pushing and maneuvering of patient beds. They are wide, measuring 1.6 m, with a sliced wall edge to ease the pushing and turning of the beds. This design ensures smooth and efficient movement, particularly during critical procedures. Additionally, the consultation rooms and medical rooms are part of a streamlined program study, optimizing their layout and functionality to enhance medical care delivery. Special 2 attention is given to ergonomics, workflow efficiency, and accessibility of medical equipment within these rooms. Moreover, a dedicated service entrance/exit is incorporated into the design to facilitate the loading and unloading of medical supplies and equipment. This separate access point ensures that logistical operations do not disrupt the flow of patient care in the main areas of the maternity center. The left wing, positioned outwardly, integrates the registration area and pharmacy for easy public access. A shared room in the center of this wing houses both the pharmacy and nurse station, allowing nurses to oversee and manage the recovery ward efficiently. This centralized arrangement is beneficial for returning mothers seeking medication and assistance, contributing to their recovery process. Moving to the rear, the recovery wards are enclosed by bamboo-woven doors and solid walls from the front entrance. The addition of fully screened shades, reminiscent of the town's bamboo fences, ensures safety and provides shading for mothers and newborns. Adjacent to these wards, there's a garden area with a serene view of the landscape, offering a peaceful setting for post-labor recovery. They create a semi-enclosed space that feels protected yet connected to the outdoors, allowing for a sense of security and tranquility. This outdoor environment aids in mental and physical recuperation, and the presence of bamboo screens crafted by community members fosters a sense of unity and support among mothers.

Interview with the team

1) Can you tell us more about your team?

1) Can you tell us more about your team?I am Ooi Yong Rong, from Penang, Malaysia. Growing up amidst the rich heritage of this city, I became intimately acquainted with its rapid evolution and the myriad issues that unfolded alongside its development. My journey as an architecture designer has been profoundly shaped by this upbringing.

2) What was your feeling when you knew you were among the top projects of the competition?

I am overwhelmed with excitement and deep gratitude. It is incredibly fulfilling to see that my work has resonated so well with the juries. This recognition not only validates the effort I have invested but also inspires me to continue pursuing excellence in my future projects.

3) Can you briefly explain the concept of your project, and which is the relationship between it and the women’s health?

The project concept revolves around prioritizing mothers' privacy while optimizing access and efficiency in medical care. The maternity center aims to provide a secure environment where mothers feel safe and protected, whether they are in labour or attending check-ups. Positioned with a blend of boldness and modesty, it achieves a balance of privacy using shades, walls, and rotating screens. The relationship with women's health lies in creating a supportive environment that enhances privacy and safety.

4) Which aspects of a design do you focus more during designing?

Efficient circulation within the center is a primary focus during the design phase. Careful planning ensures that spaces facilitate smooth movement for both patients and medical staff, enhancing overall operational efficiency and patient care experience. They should feel secure and protected under the center's roof.

5) Has your design been inspired by other projects in developing countries or past projects of Kaira Looro?

In my country, we often design shading devices to mitigate the intense sunlight. What intrigues me about this project is the opportunity it presents to integrate my own designs such as bamboo shades and rotating screens.

6) How your idea of architecture can improve health in developing countries, and how the local community concerned could perceive this architecture?

Healthcare facilities should be accessible, welcoming, and familiar to local communities, ensuring they feel comfortable and connected when accessing services. Involving community members, including local mothers, in the design and creation of features like shading devices and privacy screens fosters a sense of ownership and engagement. This participatory approach not only ensures that the design meets the specific needs and cultural preferences of the community but also empowers them to take pride in and utilize the facilities effectively.

7) From your point of view, what are the responsibilities of architects in dealing with complex issues such as health’s rights in developing countries?

Architects have the responsibility to collaboration of various sectors, gather input from various sources, considering interdisciplinary approaches to address the needs of local people. This helps to inspire their pursuit of solutions for complex issues such as health rights, exploring possibilities from a conceptual standpoint.

8) The competition registration fee was devolved to the non-profit organization Balouo Salo that helps people in disadvantage area of Senegal. How has it affected you approach to the competition?

My architectural approach focuses on creating designs that not only meet immediate needs but also endure over time, effectively serving the community for years to come. This emphasis on quality over cost ensures that the building remains a sustainable and beneficial asset to those it serves.

9) The aim of the competition is also to give professional opportunities to young architects with internship prize and visibility at international level, and we wish your team the best achievements for your career. How do you think you will be in next 10 years? According to you, can this award affect your future?

Winning an award like this could greatly influence my future by enhancing my visibility at an international level and validating the quality of my work. In the next 10 years, I will remain humble and continue to strive diligently on my architectural journey, putting my heart into achieving my long-term goals and making meaningful contributions to the field of architecture.

NICITABRI1903

from Italyproject by Nicola Brisu, Carlo Tarcisio Moi , Riccardo Ortu

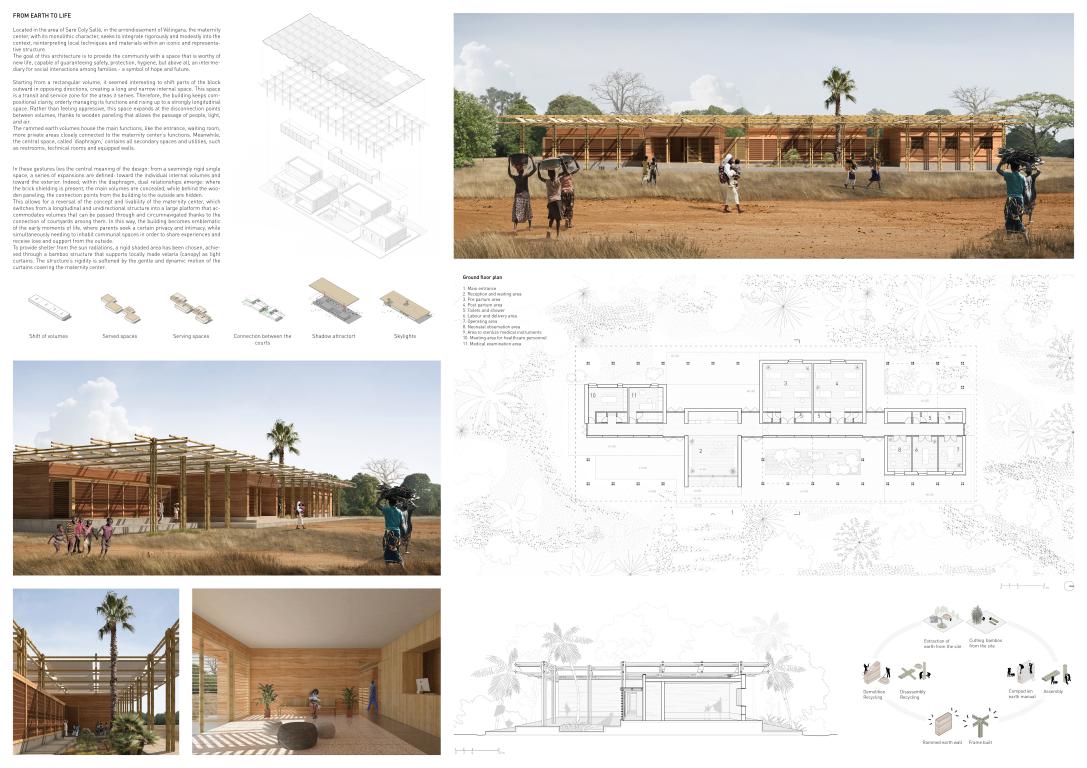

Located in the area of Sare Coly Sallé, in the arrondissement of Vélingara, the maternity center, with its monolithic character, seeks to integrate rigorously and modestly into the context, reinterpreting local techniques and materials within an iconic and representative structure. The goal of this architecture is to provide the community with a space that is worthy of new life, capable of guaranteeing safety, protection, hygiene, but above all, an intermediary for social interactions among families - a symbol of hope and future. Starting from a rectangular volume, it seemed interesting to shift parts of the block outward in opposing directions, creating a long and narrow internal space. This space is a transit and service zone for the areas it serves. Therefore, the building keeps compositional clarity, orderly managing its functions and rising up to a strongly longitudinal space. Rather than feeling oppressive, this space expands at the disconnection points between volumes, thanks to wooden paneling that allows the passage of people, light, and air. The rammed earth volumes house the main functions, like the entrance, waiting room, more private areas closely connected to the maternity center’s functions. Meanwhile, the central space, called ‘diaphragm,’ contains all secondary spaces and utilities, such as restrooms, technical rooms and equipped walls. In these gestures lies the central meaning of the design: from a seemingly rigid single space, a series of expansions are defined: toward the individual internal volumes and toward the exterior. Indeed, within the diaphragm, dual relationships emerge: where the brick shielding is present, the main volumes are concealed, while behind the wooden paneling, the connection points from the building to the outside are hidden. This allows for a reversal of the concept and livability of the maternity center, which switches from a longitudinal and unidirectional structure into a large platform that accommodates volumes that can be passed through and circumnavigated thanks to the connection of courtyards among them. In this way, the building becomes emblematic of the early moments of life, where parents seek a certain privacy and intimacy, while simultaneously needing to inhabit communal spaces in order to share experiences and receive love and support from the outside. To provide shelter from the sun radiations, a rigid shaded area has been chosen, achieved through a bamboo structure that supports locally made velaria (canopy) as light curtains. The structure’s rigidity is softened by the gentle and dynamic motion of the curtains covering the maternity center. In our material choices, we aimed to create a close relationship between ‘vernacular’ and ‘simplicity’. The selection of local materials is not only driven by practical factors such as availability and accessibility but also ethical considerations. We like to think that the building has always belonged to this region, using raw materials that require only an architectural gesture to compose them. As a result, the most common materials are used: laterite rammed earth walls define the main volumes, solid and impactful, alternated with partially perforated brick diaphragms featuring essential lattices to create a poetic and suggestive entrance for light. Internally, we opted for materials that ensure hygiene, with smooth surfaces predominantly plastered with earth and lime, especially in the delivery rooms and recovery areas. For the floors, simple tiles were chosen, following a dual chromatic scheme that differentiates between service spaces and served spaces. The roof filters the strong sunlight through a rigid and clear structure of vertical and horizontal bamboo elements, softened by a velarium system created with curtains. The project is based on a rigid 3 x 3m grid, designed to ensure order and simplicity in the construction of the building. The construction process begins with the preparation of the base, made by a mixture of earth, gravel, sand, and cement. This basement incorporates the concrete footings for the rammed earth volumes and bamboo structures. The design features dynamic extrusions and voids, creating alternating high and low platforms for circulation, inhabitation, and open spaces near the courtyards. The second step consists of marking the grid on the ground, precisely positioning the rammed earth volumes and bamboo structures. Initially, rammed earth walls are constructed, by preparing wooden molds, into which a mixture of laterite and sand is poured in approximately 15 cm layers. Then the material is compressed using a manual rammer, and pigments are added to create different colors for each layer. Between different rammed earth volumes, partitions will be prepared using brick and wooden infill for the corridor. The brick partitions will be assembled with mortar, while the wooden panels will be completely dry, with operable fixtures. These partitions consist of modules of similar dimensions for ease of construction and installation. Afterwards, it’s time for the basic horizontal closures which involve a stratigraphy of rubble stone, a layer of earth leveling, and mortar with tiles. Then the roof which features wooden beams embedded in the masonry through a wooden sleeper, a wooden deck on which an insulating layer of earth and straw is placed, and an outer layer of gravel drainage to protect the waterproofing). The construction of the building concludes with the roof structure, consisting of bamboo pillars and beams. The uprights are gathered in sets of four to facilitate connections with the beams. Curtains or veils will then be attached to these beams using simple cords.

Interview with the team

Can you tell us more about your team?

Can you tell us more about your team?We are a team of three graduate students from the University of Cagliari, Italy. We graduated a year ago and we come from the same academic background. From the beginning we understood that we could be a good group of colleagues because we are driven by the same ideas and goals of architecture.

What was your feeling when you knew you were among the top projects of the competition?

Completely unexpected! We put a lot of energy and enthusiasm into this competition but at the same time we didn't expect such a satisfactory result. We are participating in some competitions together and we are achieving good results, but this is the most important, cause it’s a very big competition and we are happy to have reached such a good position.

Can you briefly explain the concept of your project and which is the relationship between it and the women’s health?

The concept of the project starts from a rectangle, into which it seems interesting to translate some parts, generating a long and narrow internal space. This space constitutes the soul of the building, as it distributes the main rooms and allows the serviced spaces to be divided from the service ones. This approach develops the possibility of isolating the main rooms but at the same time, if necessary, connecting them. We think it is an interesting approach to guarantee sociability and community (given that the corridor opens onto the external gardens) and at the same time privacy for women. The relationship between our architecture and women's health lies in this dialectic between privacy and sociability, which in the early stages of a newborn's life are also needs of a mother.

Which aspects of a design do you focus more during designing?

When we start designing we focus on many things. First of all, we take care of the context and the goal of the project to make sure that all the community understands and appreciates it. For us, compositional and constructive clarity is very important, in this project we tried to show and share how important it is, developing an idea based on the distribution and articulation of spaces. But the most considerable approach is to work with the correct human and social identity, using traditional materials and typical architectural forms to make people absolutely fall in love with the spaces, to make sure that they will use and appreciate the building. Because a project is also a reason to improve the identity of places.

Has your design been inspired by other projects in developing countries or past projects of Kaira Looro?

In every project the first approach is to take inspiration from the context. This is why our steps started from the analysis of the general conditions of Senegal: culture, climate, materials, etc. At the same time, recent projects in developing countries have been frequent references for us, not only for the Maternity Center but in general, as a way to research and study the points of current architectural needs. This is why works like those of Francis Kéré constitute important references: for social and human purposes, but also for the use of the vernacular and techniques typical of contemporary works.

How your idea of architecture can improve health in developing countries, and how the local community concerned could perceive this architecture?

Our idea aims to improve health in developing countries because the building is easily replicable and easy to construct. The most important spaces are clean, protected and guarantee hygiene and safety, important requirements for improving health. Gardens are also important: all good architecture needs common and green spaces to improve sociality. It can be considered a sort of model that can inspire other projects: this is why we think that the project can improve health, not only in the competition area, but also in other Countries. But above all the technical choices and materials, as well as the shapes, are contextualized in such a way as to ensure that it can be part of the landscape. Furthermore, it is designed to be easily achievable, in order to guarantee that, right from the construction stages, it is shared and welcomed

From your point of view, what are the responsibilities of architects in dealing with complex issues such as health’s rights in developing countries?

The role of the architect is as beautiful and important as it is complicated and full of responsibility. Working in developing countries can be considered an exciting challenge, due to the difficulties linked to the context and economic, health and environmental conditions. The architect therefore has a great responsibility in increasing the development of these Countries, which require a 360-degree figure capable of bringing social, architectural and health aspects into dialogue. How? Proposing examples of simple, modular, replicable but above all coherent design with the history and context in which it operates, to maintain the identity of the places and at the same time improve their reality.

The competition registration fee was devolved to the non-profit organization Balouo Salo that helps people in disadvantage area of Senegal. How has it affected you approach to the competition?

It is an important initiative: knowing that the registration fee was devolved to people in disadvantage areas of Senegal can only be a source of pride, it is nice to be aware that we can contribute, in our small way, to improving these realities. It is undoubtedly connected with our vision and the mentality with which we developed the project, whose goal is to help the local community.

The aim of the competition is also to give professional opportunities to young architects with internship prize and visibility at international level, and we wish your team the best achievements for your career. How do you think you will be in next 10 years? According to you, can this award affect your future?

We are recent graduates, so it's hard to imagine ourselves in 10 years. However, we believe that the principles that currently drive us to design will remain constant in our career, which will be tortuous and complex, but hopefully full of satisfaction. We don't know how much impact this competition will have, but it seems like a good starting point for us: it gives us visibility but above all it gives us the courage to believe in our abilities and push ourselves beyond our limits.